A euphoric article by Johan Huizinga, 80 years ago.

Now we are celebrating the fifth anniversary of the reign of King Willem-Alexander, let us turn our attention to a newspaper article written to mark the birth of the King’s mother, Princess Beatrix on 31 January 1938. At that time, the economic crisis in the Netherlands was severe, unemployment high and the threat of war imminent. Over two generations the royal family, the House of Orange, had consisted of only a few members. Wilhelmina (1880-1962), Queen of the Netherlands 1898-1948, was the only child of her parents, King William III and Queen Emma. After her marriage to Prince Hendrik of Mecklenburg-Schwerin in 1901, she had several miscarriages before giving birth to their only child, Juliana (1909-2004), Queen of the Netherlands 1948-1980. Juliana’s marriage to Bernhard von Lippe-Biesterfeld on 7 January 1937 was intended to be blessed with children to safeguard the Dutch monarchy and, with that, the country itself.

Princess Juliana studied at Leiden University with great pleasure. She enjoyed her relative freedom, away from home and being together with other young female students, with whom she lived in a villa in the adjacent village of Katwijk. One of her teachers was Dr. Johan Huizinga (1872-1945), professor of general history, of national and international renown. Huizinga was in charge of presiding over the Princess’ debating club in Katwijk, where such wonderful modern topics were discussed as ‘cinema and radio as factors in present day society’, ‘The contrast between Eastern and Western culture, or ‘Modern developments in the arts’.

Alas, her freedom was to last only two years: Wilhelmina, who had become Queen at eighteen, had never herself enjoyed such a time at ease and wanted her daughter back. The University decided to distinguish the Princess with an honorary Doctor’s degree, to confirm its close relationship with the House of Orange. To Huizinga fell the delicate task of bestowing her with the degree and holding the speech. But Huizinga was used to finding the right words, without overdoing it.

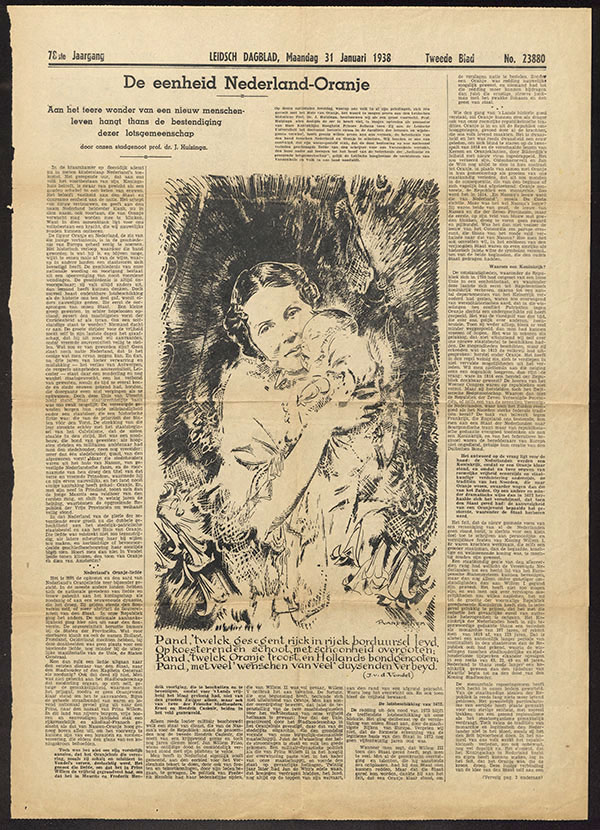

When the Princess married, she invited a German cousin to be a witness, but he was not allowed to leave Hitler’s Germany. The Princess decided to ask Huizinga in his place. She made the phone call herself, and Huizinga accepted. A year later, when the Princess was due to give birth to her first child, Huizinga wrote his ‘De Eenheid Nederland-Oranje’ (The Holland-Orange Bond), which was published in several newspapers. The illustration and the text left in the middle whether the child was a boy or a girl. His article was not about the child itself, but a short history of the bond between the country and its princely, later royal family. It is one of Huizinga’s most euphoric or impassioned articles, neglecting or simply denying any tensions, let alone divisions, in Dutch politics over the centuries. At the end of the article, he used the expression ‘it was a wonder’, characterizing the vicissitudes and qualities of the Dutch state in history, no less than seven times. In his final sentence, he changed this to ‘It is the fragile wonder of a new human life on which now depends the continuation of that beneficial and blessed community of almost four centuries: the bond between the Netherlands and the House of Orange.’